Your cart is currently empty.

A Conversation on Education and Challenges to a Successful Learning

From "Cracking the Personality Code", Chapter 18: The FACE of Education

Cathy: Why is our educational system now failing to educate almost one out of every four children in the US? Why are many more children struggling just to get by?

Gerry: To have this discussion, we’re going to have to shake things up a bit. The amount of misinformation about learning is staggering. The entire paradigm of education in the US seems to be based on a number of assumptions that are either completely outdated or wildly inaccurate.

The first assumption is the generally accepted idea that all children can successfully learn using the same educational system and those who do not succeed are somehow broken. If there is one thing I can safely say after 10 years as Director of the NLC it is that children are not all cut from the same mold and they do not all learn the same.

However, one idea I want to nip in the bud right now is the old idea of “Learning Styles”: this child is a visual learner and that child is an auditory learner. While there is an element of truth in the model, as a useful application or educational methodology, the general idea of two simple learning styles has been largely debunked.

The problem with the model was not the recognition that people have different ways of processing information: this is an important distinction. The problem is the oversimplified conclusion: that if the child is visual, you teach them visually; if the child is auditory you teach them auditorily, and so on. This conclusion was absolutely without merit, and when applied to real children, probably did more harm than good.

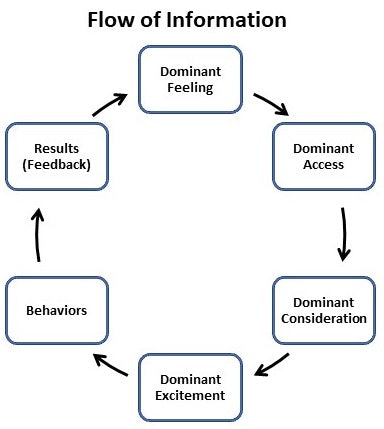

The reality is that processing information is significantly more complex, and effective education requires a model which reflects that. So, before we go any further, we should look again at the flow of information.

Now, to make this whole process easy to remember, we have packaged this process as The FACE Personality Model: Feelings, Access, Consideration, and Excitement. From this flow of sensory information we generate our behaviors, and from those behaviors, we get our results (good, bad, or indifferent).

These results become the feedback that forms the basis for the next cycle of perceiving and processing information. The FACE Personality Model identifies that our dominant personality traits occur as pairs: i.e. our dominant Feeling is either sympathetic or parasympathetic. Our Dominant Access is either visual or auditory. Our Dominant Consideration is logical or emotional and our dominant Excitement is either over-stimulated or under-stimulated.

As we’ve discussed at length, those four functions give us 16 distinct personalities or styles and each personality has four primary dominant functions: Feeling, Access, Consideration, and Excitement.

Suppose we’re in school, and our lesson for the day is to learn about the color blue. If our lenses filter out the color blue, we’re likely to have a difficult time learning about the color blue. More importantly, looking through our filter, the color blue occurs to us as the color grey and since, in our world a lot of things look grey, this information (the color blue/grey) is disregarded.

This is an important distinction, because if we do not perceive the information, we certainly can’t remember it or recall it later and it doesn’t matter what teaching method you use. If the student can’t see the color blue or sees blue as grey, it will be almost impossible to teach him the color blue.

Back to our Personality Model: neurologically speaking, our dominant Feeling is either sympathetic or parasympathetic. To see how this filter affects learning, let’s look at the characteristics of each state.

Sympathetic dominance is typically associated with our fight-or-flight emotions: anger, stress, anxiety, and fear. A sympathetic dominant person may flip-flop between being hyper-focused and oblivious to his surroundings and hyper-alert to his surroundings. He may be highly reactive to his surroundings, especially to three-dimensional visual-spatial stimulation.

In the classroom, sympathetic dominant students may have difficulty sitting still for hours. They may struggle with focus and attention. They may have trouble memorizing and recalling information, especially abstract information and as we discussed earlier, sympathetic dominant people may struggle with relationships, impulsivity, sleep, addiction and/or alcoholism. Any of these issues can have a profound effect on education and learning.

Conversely, parasympathetic dominance is generally associated with being more relaxed and focused. In the parasympathetic state, people tend to be responsive, rather than reactive. In the classroom, parasympathetic dominant students are more content to sit quietly for hours and are more apt to listen attentively to explanations, instructions, and other auditory information.

For those more familiar with the Myers-Briggs model, the behaviors typically associated with sympathetic and parasympathetic dominance are Perceiver and Judger.

When a person is in the sympathetic state, their Perception is likely to be dominant (hyper-alert) and their judgment is more likely to be weaker. Conversely, when a person is in the parasympathetic state, their Judgment is likely to be dominant (hyper-alert) and their Perception is likely to be weaker.

Again, the relevant issue is that being sympathetic dominant (Perceiver) in a typical classroom environment is almost certainly going to be a disadvantage. What’s missing in the Myers-Briggs model is that the Judger-Perceiver balance changes with your level of fear, stress, and anxiety; in other words, your sympathetic-parasympathetic state. If you are angry, or stressed (in the sympathetic state), you are going to be more of a Perceiver. If you are relaxed and focused (in the parasympathetic state), you are going to be more of a Judger.

Let’s return to education. I think we’re pretty clear on the fact that if you are parasympathetic dominant, you’re going to have a much easier time in the classroom. However, if you’re sympathetic dominant, you’re likely to have a much more difficult time.

One last note on the being sympathetic dominant: as you can imagine, very few people who are sympathetic dominant would ever want to become a teacher. As a result, almost all teachers are parasympathetic dominant. This means that very few teachers will have any real understanding or appreciation for what it means to be sympathetic dominant.

The next step in processing information in the FACE Personality Model is our Dominant Access. As we’ve discussed in previous chapters, our Dominant Access is either visual or auditory.

In the FACE Personality Model, we’ve resisted using the term “perception”, as perception implies sight or hearing as one of the five senses. As a general rule, there is no physical difference between the sight and hearing of both visually dominant and Auditory Dominant people. The difference is not in how well a person physically sees or hears the information; it’s in how that visual and auditory information is processed in the brain: how it is generalized, distorted, and filtered.

Generally speaking, visually dominant people tend to filter or generalize specific characteristics and features in favor of perceiving and recognizing patterns. This filtering applies to both auditory and visual information.

As you can guess, this filtering can have a profound effect on learning. If a child is filtering out specific phonetic sounds in favor of auditory patterns (like birds chirping or dogs barking) he is likely to be at a severe disadvantage when it comes to learning to read using any phonics-based curriculum. To add insult to injury, that same child may filter out the specific lines and characteristics of written letters, in favor of basic shapes and patterns.

This tendency to filter out characteristics and instead organize information according to patterns can prove to be another disadvantage for the visually dominant. This is because in almost every curriculum at every age, the information for almost every subject is organized, described, and tested for, according to its specific characteristics and features. The language arts are broken down into the characteristics of nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, conjunctions, etc. This is great for verbally dominant students, but terrible for the visually dominant. Why not instead describe language in terms of linguistic patterns, for example: “somebody-did something-somewhere.” This would make a huge difference to the lives of ADHD and autistic children.

Keep in mind that visually dominant persons live in a visual soup of information. Because of this, the visually dominant are generally creative, inventive, and artistic by nature. They are naturally outside-the-box thinkers and are neurologically compelled to interact, apply, do something, with the information presented to them.

As you can imagine, sitting passively in a classroom, simply memorizing and regurgitating information, especially written and verbal information, can be tortuous, painful, horrible, for visually dominant people. It is no wonder that many dyslexic, ADHD, and autistic children get labeled as trouble-makers or disruptive in the classroom.

Also, if you are visually dominant, 80% or more of your internal thoughts are occurring in your unconscious mind. You are not even aware of them, and the ones you are aware of are so flighty and so random and arbitrary that they are likely of little use in the context of a structured lesson. They are more likely to be annoying to the teacher and even your classmates. Your best results may come from being the class comedian. But since your visual memory is disorganized and of seemingly little use, you are more likely to follow suit with everyone else in class try to learn auditorily. This is not a conscious decision: it’s a matter of survival. You are going to try to read, memorize, and recall information auditorily because, for all practical purposes, your visual memory – your ability to take an image and hold it steady for even a few seconds – is simply not reliable.

Can you imagine trying to pay attention to a teacher rambling on about this and that, speaking at 3 to 4 words per second, while your brain is generating this visual soup at a rate of 30 to 40 images per second? Can you imagine having to filter out or filter through 30 to 40 images per second just keep track of and memorize what the teacher is saying?

Cathy: That’s pretty good. When you were able to figure out that I was visual-spatial, what that did is give you the goal for me, a direction to coach me in, right?

Gerry: It gave me a place to look, it gave me the idea to look and probe to see where you might be not as successful as you want to be so, I wasn’t just making stuff up, I wasn’t looking for problems, I was just probing and letting you tell me where or what the problem might be. It was all based on what you wanted to change, so very rarely I would suggest changes without you bringing it up because it generally didn’t work if you weren’t ready for it. It didn’t matter what I saw: what mattered was what you saw, and you don’t know when I saw certain things because I didn’t tell you about everything. What I told you about was mostly what you told me, and I would paraphrase it.

Cathy: So even though you could see the things that I needed to do, you didn’t address it?

Gerry: That’s not to say I might not nudge you in that direction but still I think it’s important in most cases, and like I said I did both ways with more than one client; I tried to lead the horse to water and make them drink. It never worked so, lead the horse to water and let them decide when they are ready to drink or not. The funny thing is that there are things that I said to you numerous times over the years and all of the sudden one day out of the blue – and I wish I could remember one of the quotes – you were all excited and you said “my gosh I am like this!” like it was a big surprise to you. One of them was that you had this friend that needs you more than you need him and I must have said that a dozen times over the years and then one day you’re like “you know I think he needs me more than I need him.”

Cathy: That was definitely true: I remember you telling me that and I didn’t believe you! Now tell me where you got that from?

Gerry: What I saw was that you would describe something like his behavior and his behavior was very inconsistent and you would focus on the negative behavior maybe. You’d also ignore some of the positive behaviors or subtleties like you’d get upset when he might say we can’t talk for a while. I would say wait, he’ll call, and he would, he would show up at your door basically. You would be thinking that it’s the end of the world and days later he shows up at your door.

Cathy: So part of that was me not recognizing my own value.

Gerry: Not recognizing your own value, focusing on the negatives, I would say that’s all I need to say about that.

Cathy: So that’s just one example: as all coaches do, you were seeing the good in the person they are coaching.

Gerry: Well you see it from the outside. Ideally, they see everything from a neutral perspective. And I don’t know that you keep pointing at that…

Cathy: But this is a potential like you were talking about: that fully-actualized person.

Gerry: No wait that’s not what I am saying there. That is who you are wired up to be neurologically: the behavior is the potential, what you can do with it. It’s your behaviors you can work with and the sad thing is that most therapists, coaches and counselors don’t see that at all, they don’t see this model, this entire thing that we are talking about.

Cathy: There is another book from which I just want to bring up a concept of “strength finder”. So the concept of this person is that instead of trying to fix your faults you realize your strengths and what you can do with your strengths.

Gerry: I agree with that a thousand percent.

Cathy: Because what he says is something you said: “you can spend hours and hours trying to fix some things that you are not good at but it’s really a waste of time when, if you focus on your strengths” and now I see why this works is because this is probably related to brain function.

Gerry: Here is a great example of that. When a child is tested and is shown to be dyslexic the standard protocol is to spend hours and hours trying to teach that kid to read auditorily. The Lindamood-Bell and Orton-Gillingham are two of the methods that schools use, Orton-Gillingham is really common and they are recognized as standard for dyslexia. Their own research says that this will take anywhere from 80 to 180 hours to improve reading substantially whatever the measurement is, and what they do is that they beat the child over the head with phonics hour after hour, phonics upon phonics upon phonics and eventually, yes the child does learn to read around 180 words per minute.

What I did in the NLC for almost a decade, was to take that child and with 4 to 5 hours, improve their reading speed by a 100% or more. How did I do that? Am I the miracle worker? All the popular research says you can’t do that. A dyslexic child can’t just read but, I did it and the reason I did it was because I looked at how they processed information and that is visually. I gave them a visual map of the alphabet, not an auditory map generated from speech and sound. I gave them a 3D visual map that they constructed out of clay or play dough.

I corrected the false information in their brain and lack of information with respect to letters, because I knew that they used pattern recognition rather than characteristics to see things. So, rather than try to change that, I adjusted the learning of reading to suit the way they processed information.

Cathy: When you gave them that clay to make the letters did you attach the sound to the letters?

Gerry: I didn’t have to because once you have the map of the alphabet clearly in your head especially at that age, as those are not kids at kindergarten; if you can say: “the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog” this has all the sounds of the alphabet. It doesn’t have some of the subtleties, the exceptions for spelling or whatnot, but it has sounds so, if you can say that sentence, for all practical purposes you have every sound that you need to read. There are going to be some exceptions, but here is the thing: we are not going to try to teach the child to read using phonics. We are not going to try to teach the child to read based on how words sound and this is covered in my book Reading with Dyslexia.

For all practical purposes, the way we are taught to read is that we look at the first letter in that word. We see a letter and we process that letter visually and then we bring it over to the other side of the brain to see what sound that letter makes in memory and then we go to the next letter and we see what sound that letter makes and we also have to compare first two letters because they might go together like “ch” or “st” and then we do the same thing and then we get to next sound and then we have to double check to make sure it’s not another sound like “str” or “sch”.

We have to do this circular iteration with each letter all the way to the end of the word, and eventually we get to spell out “school”. From the sound of the word we construct; if we get it right, we then retrieve from the visual-spatial memory the meaning of that word. That’s a lot of work, especially if your brain is operating at 30 images per second and it’s trying to make sense of all this so by the time you get to three of those words you don’t even know what you read. It’s just nonsense.

Let’s assume that you do read that well, you endure the torture of phonics coaching for 80 to 180 hours and you do start to read phonetically. Guess what? By the time you are done with that sentence you don’t even know what you read because your brain has been so engaged in processing these sounds and images.

So, the approach I take is you learn a visual, 3D model of the alphabet and then the way you learn your words is by learning the whole word as a picture. For example, take the word “school”. It’s on a flash card. Instead of memorizing the word as a series of letters, or worse, as a series of phonetic rules, you turn the word into a picture, a visual image, and guess what? You take the meaning of the word “school” and you make a picture of that. So now the word and the meaning of the word are both images. They are both in the visual storage in your brain.

Now your brain doesn’t have to go back and forth from visual to auditory, auditory to visual, decoding and deconstructing and then reconstructing to get this word “school” and then retrieve the image from another part of your brain. Instead, we’ll take the word “school” and take an image of the meaning of school and put them together in the very same memory. How do you think that will affect your reading, your learning, your education if we retrain these visual thinkers to use their visual memory in such a way that the words and the meaning of the words are literally in the same memory. How much easier and more efficient and enjoyable will their education be?

The intention here is to help parents understand that progress and success are not as far off as they may have thought. These flexible programs allow children to progress at their own pace and utilize their natural gifts in new ways which allow them to succeed and grow.

Summary

In working with these children, we’ve realized that many of the difficulties that they experience later in life could have been prevented or significantly lessened with simple, early treatments. These early treatments can begin long before conventional diagnosis is possible.

The reason for this is that early in life, children develop specific mental patterns (strategies) for processing various types of sensory information. These strategies, when employed successfully by the child in specific circumstances, can become generalized to situations where they may not be effective.

In addition, as children grow, they may develop particular solutions to situations when their primary strategy is ineffective. These solutions often become compulsive behaviors which are often of little or no practical use later in the child’s life. The combination of the inappropriate use of mental strategies and the development of compulsive behaviors can severely impact a child’s effectiveness.

While conventional diagnosis may not be possible until a child is older, identifying a child’s learning style at an early age (2-6) can allow for early intervention and greater success. Some of the characteristics of at-risk children include:

- Delayed speech or language skills

- Difficulty processing auditory information

- Unusual or delayed social behaviors

- Difficulty with transitions from one activity to another

- Above average visual or spatial awareness

- Above average intelligence

- Eye tracking problems

- Delayed midline integration

- Delayed fine or gross motor skills

- Difficulty with reading or reading comprehension

- Dislikes reading but enjoys being read to

- Stutters

- Forgetful, difficulty remembering

- Avoids eye contact

- Frequently tunes out what’s happening

- Watches what others are doing or needs to see gestures before following directions

- One or both parents having dyslexia, ADHDor other sensory processing disorders

- One or more grandparents, siblings or other close relatives having dyslexia, ADHDor other sensory processing disorders

Children with two or more of these characteristics may be at-risk for some type of specific sensory processing issue. The good news is that early intervention can help alleviate many of the difficulties that are often the result of sensory processing or sensory integration issues.

In addition to its reading, writing, and mathematics programs, NLC recently introduced its Early Childhood Neuro-Sensory Development Program for at-risk children. The program is designed to assist parents in identifying young children, ages 2 to 6, who are at-risk for developing specific sensory processing problems.

Obviously, this brief text was not intended to answer everyone’s questions about learning challenges. The complexities of these various conditions and the challenges they present is beyond the scope of any single text. Our primary intent was to offer hope to those struggling with the effects of sensory-based learning challenges, relating them to the FACE Personality Model.

For more information on education and overcoming the most common learning challenges, visit us at www.swishforfish.com.

Leave a Reply